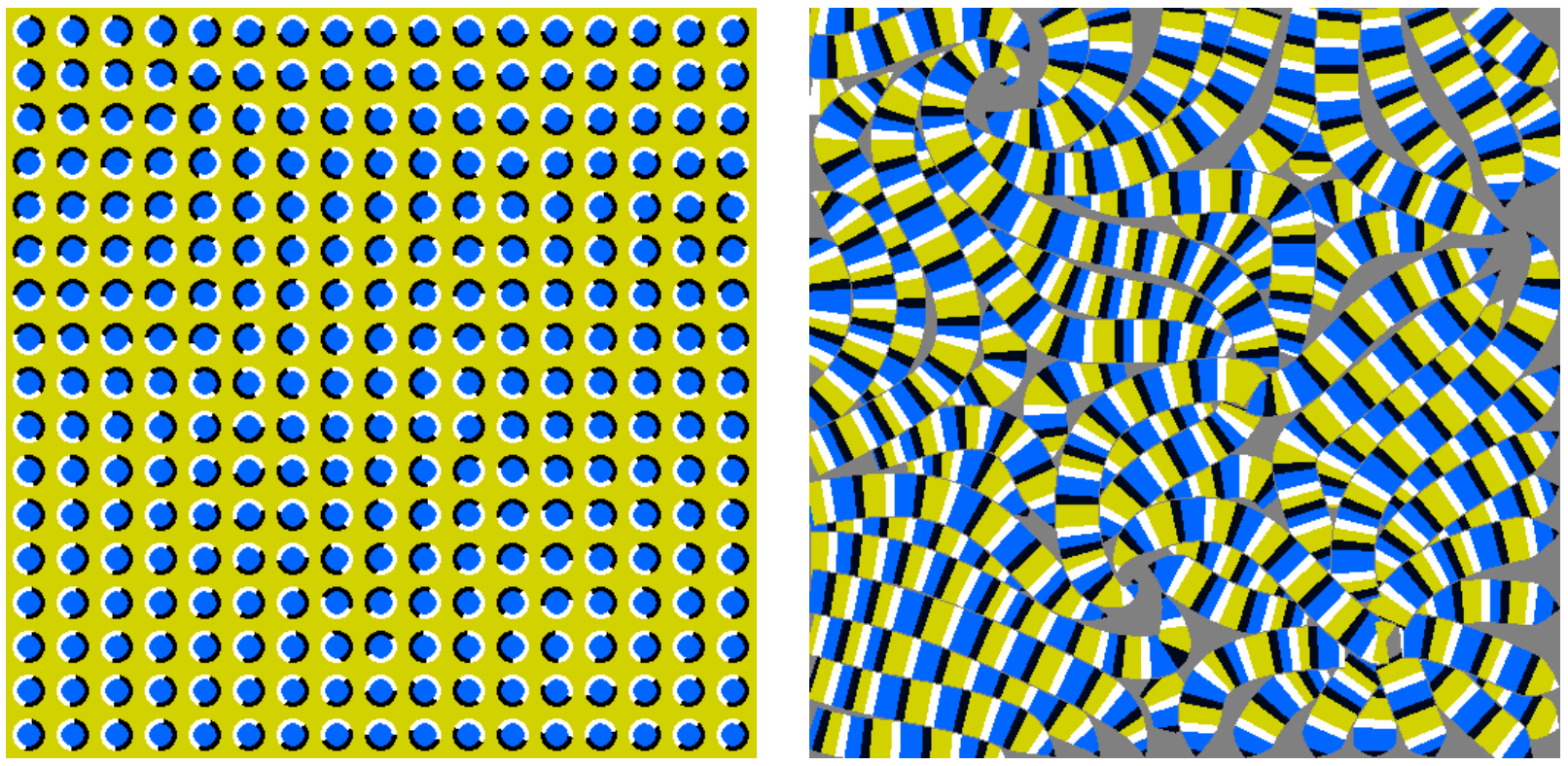

Self-Animating Images: The pictures appear to creep because of the arrangement of colors in the small small repeated patterns. Combination of 4 colors gives the best illusion. These 4 colors should be as different from each other as is possible

Our natural feeling is that our minds are like a mirror on which light falls – that we simply perceive the world as it is. For a long time, philosophers and scientists thought along similar lines. In the late eighteenth century Immanuel Kant introduced the idea that there is a stage between what our eyes and ears pick up and what we perceive; that while we depend on sensory data for our knowledge, we make sense of its profusion and confusion by relying on in-built mental categories. But it took scientists science some time scientists to catch up with Kant; in classical physiology up until the twentieth century, visual images fell upon the optic nerve, and that was that. Freud suspected that the function of receiving sensory signals and registering them were separate, though he had no strong evidence for it at the time. We now know that the brain does indeed do a lot of work to make reality comprehensible- that the world as scanned by our eyes is rather different from the world we see. Your brain “serves up a story to you”. In a sense, deception begins the moment you open your eyes. (Ian Leslie “BORN LIARS”)

A dizzying spiral pattern vividly activates Francis Stark‘s Chorus Girl works, generating the illusion of their mobility. (Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 2017) The pattern based on well-known work Rotating Snake by Akiyoshi Kitaoka.

If you stare at a fixed point in space, like a dot on the wall in front of you, everything to the left of the do is projected to the right half of your brain, and vice versa. each hemisphere receives nerve transmissions from the opposite leg and arm and picks up sound from the opposite ear. Nobody knows why, they just do.

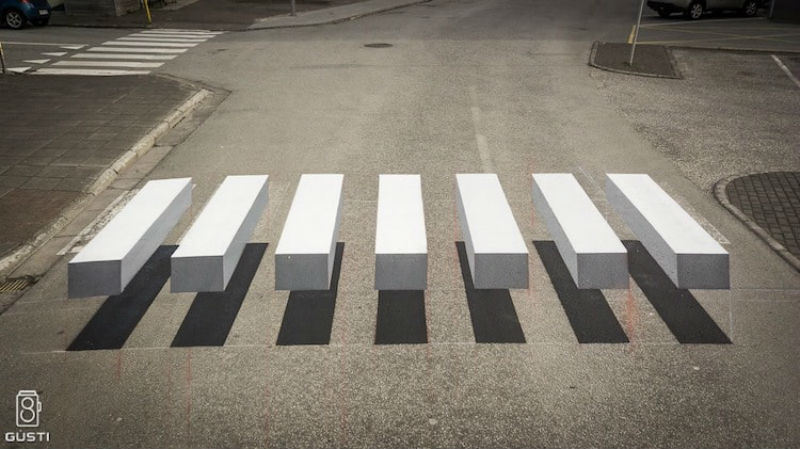

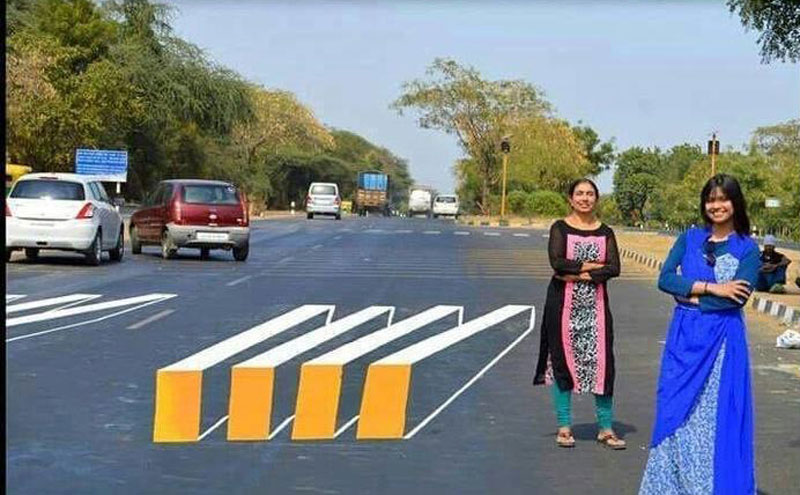

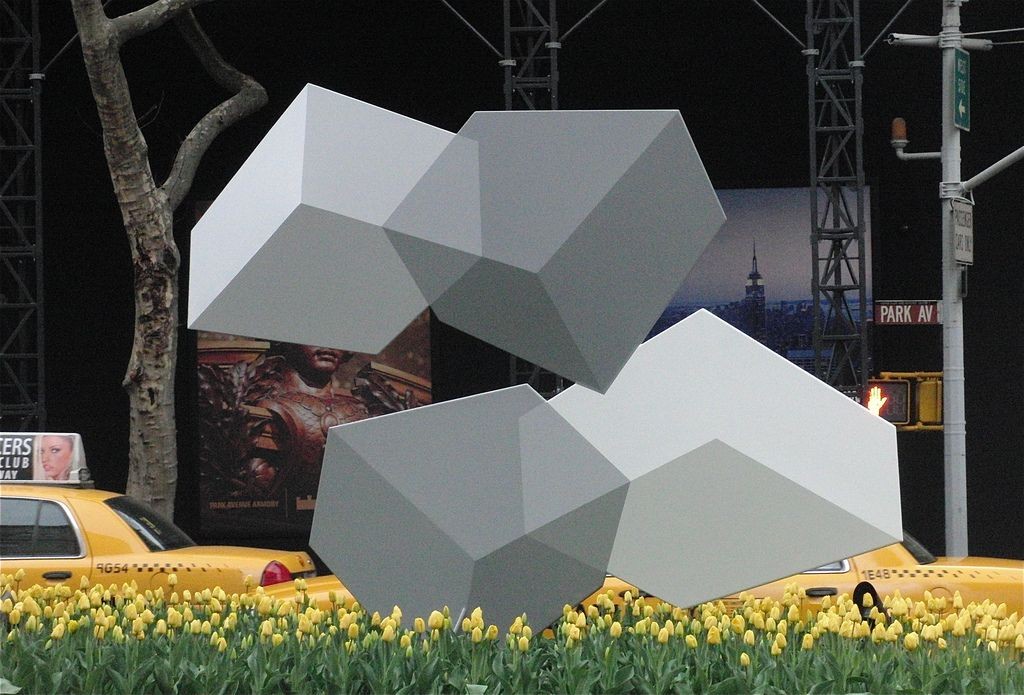

Slender works by Venezuelan-American artist Rafael Barrios play like a 3D optical illusion (New York, 2012)

Your eyes don’t have enough neuronal receptors to capture a whole property, so pupils dance frantically around as they try to bring the sharper region of focus to bear every part of the room, a movement known as the saccade. Yet you have the illusion of continuous, coherent vision.

The brain ‘actively creates pictures of the world’. Rather than trying to interpret every new thing it sees as if encountering it for the first time, the brain makes series of working assumptions about what a chair looks like, or a person, and where object going to be, then makes predictions about- best guesses- about what’s before us. It compares its expectations with the new information coming in, checks for mistakes, and revises accordingly. The result is ‘a fantasy that collides with reality’.